We are on a journey, a transition from health records being recorded on paper to a new paradigm of electronic health records (EHRs) and data interoperability.

We’ve all grown up in an era of paper records – the inability to read doctor’s handwriting, lost records, flood damage and overloaded filing cabinets have been the norm for decades. This is our common experience all over the world.

While they have been in use for much longer, it is only in the last 20 years that electronic health records have slowly been encroaching in everyday clinical practice, accelerating markedly in the last 5 or so. There are some areas where the benefits of electronic records have been a no brainer – for example, ability to generate repeat prescriptions in primary care were a major enabler in the mid 1990’s here in Australia. Yet despite some wins, the transition to EHRs has generally been much slower than we anticipated, much harder than we imagined, and it is not hard to argue that interoperability of granular health data remains frustratingly elusive.

But why? Why is it so hard?

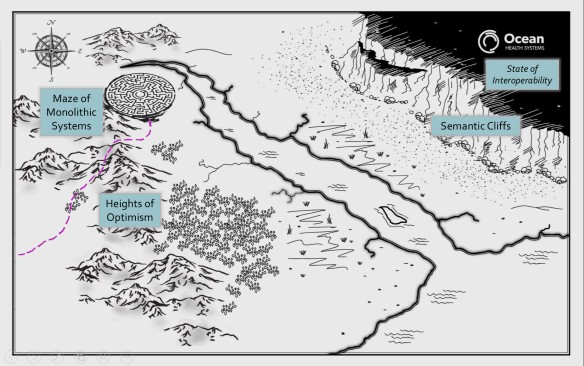

Let’s start to explore this question using this map – paper records represented by the ‘Land of Missing Files’ in the left bottom corner and the ‘Kingdom of Data’ on the remainder of the map.

The ‘Kingdom of Data’ can be further divided into two – the ‘State of Connectivity’ and the ‘State of Interoperability’ which is located on top of the ‘Semantic Cliffs’.

Universally, our eHealth journey commenced in the Land of Missing Files, crossing through the ‘Heights of Optimism’ and dividing into two major paths.

The first path heads north to the ‘Maze of Monolithic Systems’ – the massive clinical solutions designed explicitly to encompass clinical needs across a whole health organisation or region – think Epic or Cerner as examples. These systems may indeed provide some degree of connected electronic data across many departments as they will all use a common proprietary data model but departments that have different data or functional requirements are effectively marooned and isolated outside the monolith and there is enormous difficulty, time and cost in connecting them. The other harsh reality is that is often extremely difficult to extract data or to share data to the community of care that exists outside the scope of the monoliths influence. Historically the monolith vendors have been notorious for saying ‘if you want interoperability, buy more of my system’. It is likely that this attitude is softening but, due to the sheer size of these systems, any change requires months to years to implement plus huge $$$ .

The second path heads east to the ‘Forest of Solo Silos’. Historically this has been the natural starting point for most clinical system development, resulting in a massive number of focused software applications that have been created to solve a specific clinical purpose by well-meaning vendors but each with its own unique proprietary data model. Each data model has traditionally been regarded as superior to others and thus a commercial advantage to the vendor – the truth is that none of them are likely to be better than another, all built from the sole perspective of the developer alone and usually with limited clinician input.

Historically, our first priority was to simply turn paper health records into electronic ones – capture, storage and display – and we have been successful. However the systems we built were rarely designed with a vision of how we might collectively use this health information for other more innovative purposes such as data exchange, aggregation, analysis and knowledge-based activities such as decision support and research. This is still well entrenched – modern systems these days are still being built as silos with a local, proprietary data models and yet we still wonder why we can’t accurately and safely interoperate with health data.

In order to break through the limitations and challenges imposed by the solo silo and monolith approaches we have collectively trekked onwards into the ‘Swamp of Incremental Innovation’. It is a natural human trait to try to improve on what we have already built by implementing a series of safe incremental steps to extend the status quo. We have become very adept at this – small innovations building on the successful ones that have come before. And the results have been proportional – small improvements that have been glacially slow in development and adoption – and one key factor has been because we have been held back by our historical preference for disparate, closed commercial data models.

The natural consequence of incremental innovation on our journey to interoperability is that we are constantly looking down, looking where we will place our immediate next step, rather than raising our heads to see the looming ‘Semantic Cliffs’. I think that the large majority of vendors are stuck in this swamp, taking one step at a time and without any vision of strategy for the journey ahead. Clinical system purchasers are perpetuating this approach – just look at the number of jurisdictions procuring the monolithic systems. Nearly every other business abandoned this approach decades ago… except health.

We run the risk of becoming permanently stuck in this swamp, moving in never-ending circles or hitting the bottom of the Semantic Cliffs with nowhere to go and drowning in the ‘Quicksand of Despair’.

Beware, my colleagues, here be dragons!

We need a Bridge of Smart Data! A shared and semantically accurate, safe and unambiguous data foundation that we use as the basis for all eHealth activities: for persistence; exchange; aggregation and analysis; decision support AND research.

We need a Bridge of Smart Data! A shared and semantically accurate, safe and unambiguous data foundation that we use as the basis for all eHealth activities: for persistence; exchange; aggregation and analysis; decision support AND research.